One of the things I noticed while going over the 2017-2018 releases from the ARC was a set of FBI files on a man named John Caesar (or Cesar) Grossi. These files turned out to be suprisingly numerous and hard to keep track of. Based on some of the work I’ve done recently, I now have a much better understanding of why that was so.

The Grossi files are interesting not for their relevance to the JFK assassination, but for what they show of the range of materials in the ARC. They are also interesting examples of some of the more complex reasons why the FBI withheld Collection records, and how they eventually came to release them. This lengthy post will therefore cover both what I found in Grossi’s files, and what I found out about how they were handled.

John Cesar Grossi and the JFK assassination

Grossi is not an important figure in the JFK assassination investigation. His only appearance is as Lee Harvey Oswald’s co-worker at Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall (JCS), a graphic arts company in Dallas where Oswald worked for a few months.1CE 427 (17 H 156) gives October 12, 1962 as Oswald’s date of employment and has a note that he was terminated April 6, 1963. Testimony from several JCS employees can be found in 10 H 167-213. For those looking up JCS online, Jaggars is very frequently misspelled “Jaggers”. The correct spelling, as given in the WC hearings, is with an “a”.

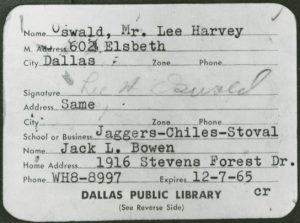

Grossi was employed at JCS under the name of Jack Leslie Bowen. The fact that Oswald met Grossi/Bowen is registered on Oswald’s Dallas Municipal Library card, which, in addition to Oswald’s name and address, also gives Grossi/Bowen’s name, address, and phone number.

Lee Harvey Oswald Dallas Library card

Why? Oswald needed a sponsor to get a card and coworker Bowen/Grossi agreed to sponsor him. All of this is documented in Oswald’s Dallas FBI file.2The file in excerpted in Commission Document 205, p. 469

The Grossi “Subject files”

Explaining Bowen’s name on the card takes up all of two pages in the Oswald file. So what are 1000-plus pages from a half dozen FBI files on Grossi doing in the ARC?

These files belong to a set of FBI documents called the “FBI-HSCA Subject Files.” They are files on people, organizations, and subjects that the HSCA asked the FBI to provide during their investigation of the Kennedy and King assassinations. As I have noted in earlier posts, many of these people and/or subjects are marginal to the JFK (and King) assassinations. Grossi is one such marginal figure. What then do the files on him reveal? Almost nothing, as far as the JFK assassination is concerned. But that does not mean they are boring reading.

Instead, they turn out to be a vivid portrait of John Grossi and his checkered career over a period of 30 years. There are many gaps, of course, since the FBI only investigates certain types of crimes. Nonetheless, there is enough material to cover significant spans of Grossi’s life, and it is so colorful that Grossi himself apparently thought of writing an autobiography at one point.3ARC record 124-10208-10266, p. 17

In keeping with the boring tradition of this website, after summarizing the really interesting stuff, I will focus on the boring question of how this material got into the ARC in the first place, and how it was slowly released over a period of 25 years. In this case, however, there is so much material in the files that the summary is going to stretch over two very long posts. The main Grossi files I will discuss are the first two chronologically: 43-5359 and 88-30913.

File 1: On the Road

The earliest FBI file on Grossi, case no. 43-5359, was heavily redacted prior to the 2017-2018 ARC releases because the first ten or so documents cover his juvenile criminal record. (See below for a discussion on how the ARC handled such records.) These documents have now been released in full so that, with one exception, the entire file is open.

The file begins with the arrests of Thomas Herman and Jack Dale Williams for Illegal Wearing of Uniform (IWU) on March 29, 1944 at Savannah, Georgia.4FBI file 43-5359-1, released as ARC record 124-10204-10223. This is one of the few examples in the ARC of an FBI case file for IWU (classification 43), which is to be distinguished from impersonation (classification 47). Apparently impersonation was more serious, but also more difficult to prove. In the end, however, through an odd fluke, Grossi was nailed not for IWU, but for impersonation. See Haines, Gerald K., and David A. Langbart. Unlocking the Files of the FBI: A Guide to Its Records and Classification System. Scholarly resources, 1993 for a general description of the category.

Sharp-eyed MPs noted their uniforms were incomplete and the two were soon in the lockup. Herman, 17, admits in his statement to Savannah Special Agent (SA) Sims that he is on leave from the Merchant Marines, yet is wearing a U.S. Navy uniform. His shipmate Williams is in bigger trouble. He is not only wearing a Navy uniform, he has already turned eighteen, yet failed to register for the draft. Both men write detailed statements explaining how they got leave while their ship was in port and acquired illegal uniforms.

The very next “serial” (as the separate documents in an FBI file are called) reveals that “Williams” is not Williams, but Jack Grossi.5FBI file number 43-5359-2, released as ARC record 124-10204-10224 He is not 18, but 16. He was not wearing a Navy uniform, (Merchant Marine and Navy uniforms have subtle, esoteric distinctions) and neither of the two is on leave from the Merchant Marines, or even in the Merchant Marines. They are runaways from New Jersey who have been hitchhiking around the country wearing the uniforms to get rides and handouts from sympathetic strangers.

Herman is given two years probation for the IWU rap. Charges against Grossi are dropped, but he is held pending investigation when they discover he is actually a fugitive from the State Home for Boys in Jamesburg, NJ.

The next document presents the result of the FBI’s investigation into Grossi’s background.6FBI file number 43-5359-3, released as ARC record 124-10204-10225. It gives a sad account of his childhood and family. Most of the information comes from Grossi’s New Jersey probation officer, who has no good opinion of anyone in the Grossi family. Father, mother, and older brother all have arrest records, and his older sister is “of poor moral character and lucky not to have acquired a criminal record at this time.”

In addition to Grossi’s outlaw genes, one perhaps should mention that his parents divorced when he was eight. Some of the father’s legal troubles had to do with failure to pay support, while his mother had at least one arrest for child neglect.

The record of Grossi’s outlaw career begins in 1942, when he is charged with stealing nine dollars worth of war stamps at the age of 14. He is put on probation, which he repeatedly violates. After a few months of this, he is made a ward of the court and put in a series of foster homes. Alas, he continues in his “nefarious ways” and in March 1943 winds up in New Jersey’s Jamesburg reformatory. By August he has had enough and “escapes.” He is arrested and fingerprinted in Media, PA, then sent back to Jamesburg.7This comes from 43-5359-25, released as ARC record 124-10204-10250. Since Grossi was 15 at the time, this was also treated as a juvenile record and withheld until 2018, when these redactions were finally released by NARA He manages to last another six months before he takes off again in March 1944, eventually ending up in Savannah.

So what will young Grossi’s fate be? The investigating SA informs Jamesburg that Savannah isn’t going to hold Grossi. Jamesburg Superintendent Fitch informs the agent that it is too far to come for Grossi and they don’t want him either. The report closes with the traditional FBI valediction for the end of a long correspondence: Referred Upon Completion to Office of Origin (RUC).

The next document is a formal one page epilogue to Grossi’s saga: “In view of the fact that all logical leads have been covered, this case is closed.”8FBI file number 43-5359-4, released as ARC record 124-10204-10227. How wrong they were! Over a hundred pages still remain to go.

Grossi redux

Mysteriously, unlike Grossi’s other juvenile records, the next document in the file, serial five, was not released in 2017-2018. According to the file inventory for 43-5359 at the Mary Ferrell Foundation, however, it is a one page memo from Savannah to HQ sent on 7/7/1944.9The inventory is apparently not part of the ARC This must have been a response to the next item in the file.

The next item is a one page teletype from New Orleans sent on 7/5/1944, informing HQ that Grossi was arrested in New Orleans on July 4th for wearing the uniform of a Chief petty officer in the Merchant Marines, and is now in NO parish prison, charged under the federal Juvenile Delinquency Act (JDA).10FBI file number 43-5359-6, released as ARC record 124-10204-10229. And just one week after Savannah closed the case.

The teletype is quickly followed by a lengthy report from New Orleans SA George Smith.11FBI file number 43-5359-7, released as ARC record 124-10204-10230. Grossi gives Smith a highly edited version of his back story, recounting only one stay with a foster family, leaving out his arrest in Media PA, and so on. Departing the Jamesburg NJ reformatory, Grossi relates, he took busses through Philadelphia, Baltimore, Raleigh NC, and Charleston SC before washing up in Savannah. In Savannah he was released because he was underage, and told to go back to Paterson NJ where his mother lives. He promptly took the next bus to Jacksonville FL and bought the illicit Chief petty officer outfit.

Smith’s report provides details of Grossi’s modus operandi, which has changed since his previous arrest three months earlier. He now has identification papers for his Jack Dale Williams persona, which he is still using. These include an id card which says he is a member of the USMS, two typewritten statements introducing “Williams” and a handwritten letter from “Captain Fitch” addressed to “Williams”, giving him leave until April 1944. He also has a silver bracelet with Williams’ name and USMS serial number on it.

Smith’s report also provides interesting details on how Grossi is financing his travels. Grossi states that he raised about $200 by selling his war bonds, bought with earnings from the diner where Jamesburg had arranged work. He also has three tickets from three different pawnshops in Savannah, which show he raised $30 by pawning a watch, a clarinet, and a phonograph. These were personal items he took with him when he left Jamesburg (none are mentioned in his Savannah arrest record). The ticket dates place him in Savannah up until June 20. Smith’s report ends with a suspenseful “PENDING.”

The suspense is resolved quickly with the next document.12FBI file number 43-5359-8, released as ARC record 124-10204-10232. After a couple of weeks in the the parish jail, Grossi consents to trial under the JDA. He is convicted and sentenced to seven days. Apparently they tried to arrange for him to actually join the USMS, but the probation officer reports that Grossi is not acceptable. He is “referred to a local social service institute to obtain suitable employment” in NO. This is our last glimpse of the 16 year old Grossi. He turns 17 in the NO parish jail. Sans suitable employment, he then moves on.

Seventeen

The FBI records on Grossi in the ARC have little to say about the 17 year old Grossi. His rap sheet show that he was fingerprinted when he applied for a job as a hotel porter in Miami on 12/1/1944. He was fingerprinted and held for “investigation” in Shreveport, LA on 2/5/1945 under the name of Rodger Garland Dieckman.13See the 2018 release of ARC document 124-10204-10250 He was released after five days without charge. Later documents in the file also give hints of Grossi’s activities in Baltimore and Dallas during this time.

Heading for the big time

In August 1945, Grossi turns 18. It is at this point that he discovers the joys of writing fraudulent checks, and by December 1945, his checks are bouncing from Philadelphia to Baltimore, Detroit, Chicago, Atlanta, and Dallas, keeping the FBI offices in these places surprisingly busy.

No longer a juvenile, the remainder of Grossi’s file has been avilable in the ARC since 1995. Still, putting together the pieces of case number 43-5359 is not easy; field office teletypes are mostly not included in the file, and longer documents, reports and memos, were all written after February 1946, so that it is hard to tell when the FBI found out about what.

Stopover in Baltimore

The first report on Grossi’s new hobby of paper hanging comes from the Philadelphia FBI office.14FBI file number 43-5359-9, released as ARC record 124-10204-10234. According to Albert Menger, secretary of the Army-Navy YMCA in Philadelphia, Grossi checked into the Y on December 5, staying through the 6th.

Grossi and two friends first go to Joe Kors, who has a novelty shop in the locker room at the Y, and buy a “serviceman’s plaque” Not having enough for a deposit on the plaque, Grossi asks Kors to cash a check. Kors sends Grossi to Menger. Through some sixth sense, Menger declines to cash any checks for Grossi, who then goes back to Kors, and shows him a bank statement indicating he has $1000 dollars in the First National Bank of Dallas. Kors figures no problem, cashes the check and takes down an address in Dallas to send the plaque when it was ready. Having found a rube, Grossi goes back the next day and gives Kors five dollars to cash another check. Total damage to Kors, $42.00.

Appointment in Detroit

The next item is from Detroit.15FBI file number 43-5359-10, released as ARC record 124-10204-10235. On December 10th Grossi visits the home of Detroit resident Otto Ziegler in the company of Chester McEwing, a navy friend of Ziegler’s son. Grossi is wearing a uniform with a row of campaign ribbons, so of course the accommodating Ziegler helps Grossi cash almost $400 worth of checks written on his non-existent bank account at the First National Bank of Dallas. Grossi departs, leaving only a forwarding address at Brooklyn Shipyard, a home address in Dallas, and a copy of a letter granting him leave for 45 days

The FBI’s Washington Field Office quickly discovers that the naval serial number on the leave notice belongs to someone in Los Angeles and that there is no record of a John Grossi in the U.S. Navy. WFO tells New York to check out McEwing, who it turns out was with Grossi in Philadelphia when Grossi scammed Joe Kors and travelled with Grossi from Philly to D.C. to Detroit, to Newark, to Baltimore, where Grossi and his wife reside, before returning to his base at Staten Island. Unlike Grossi, McEwing really is a sailor in the USN.

From New York, calls go out to the Detroit, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Dallas offices. Dallas reports that Grossi’s “home” address is the residence of Harold Van Buren, who had previously employed Grossi sometime in 1945, and knows a fair amount about Grossi’s true background. Van Buren apparently feels sympathetic toward Grossi, despite getting stuck with another Grossi check for $100.

Meanwhile, the Michigan AUSA (Assistant US Attorney) decides he’s got enough to issue a warrant for Grossi on impersonation charges. (Writing a forest of fake checks is NOT a federal offense.) The warrant is sent to Detroit and returned non est (Latin for ‘never heard of the guy’). The hunt is on!

… and ends in the next item. Grossi is arrested in Chicago on February 14th and admits passing over $700 in bad checks.16FBI file number 43-5359-11, released as ARC record 124-10204-10236 He does not, however, admit to impersonation, and gives an account of his naval service that this Chicago teletype asks HQ to check out.

A flurry of teletypes to and from the FBI lab follow, checking the handwriting and physical details on bad checks written by Grossi. There is also a memo from Atlanta to HQ, reporting another bad check Grossi wrote for a leather sports jacket.17The lab requests and reports include FBI file number 43-5359-12, released as ARC record 124-10204-10237, FBI file number 43-5359-13, released as ARC record 124-10204-10238, and FBI file number 43-5359-14, released as ARC record 124-10204-10239. The Atlanta report is FBI file number 43-5359-15, released as ARC record 124-10204-10240

A Dallas connection

The chronology of the next several items in the file is not clear to me; for this post, I’ll mostly follow the order in the file. Next up: a follow-up report from Dallas on the “serviceman’s plaque” Grossi bought in Philly and had sent to an address in Dallas.18FBI file number 43-5359-16, released as ARC record 124-10204-10241

The address turns out to be the apartment of Mrs. HB and her daughter MB. MB met Grossi at the Dallas USO in October 1945 and since then he has visited their apartment several times, staying for as long as a week in November. He has left a bag at their apartment containing a navy uniform, a parachute from Maxwell Air Field, AL, and a 12-inch record of a radio program called “Glamour Manor.”

MB has received two letters from Grossi in December. Both have Philadelphia return addresses. Interestingly, Grossi writes in these letters about getting work as a cartoonist. This later becomes Grossi’s main source of legitimate work, and is the reason he was employed at Jaggars, Chiles, and Stovall in the early 1960s.

MB apparently took the letters in a positive light and wrote to Grossi’s mother, now remarried. The former Mrs. G. responded promptly. Her letter “advised in substance that subject was absolutely no good and there was nothing she could do about it; that he had been running around the country for the past two years; that [MB] was only one of many from whom she had received letters; that subject was married in Philadelphia in November and his wife’s address was …”

MB’s interview closes with her assurance that “she would immediately notify this office upon receipt of any information concerning the whereabouts of the subject.” One can hardly blame her.

The report also gives a transcript of the “Glamour Manor” record, dated August 22, 1945.19The “Glamour Manor” program is now lost in mists of history, except to the fans of old time radio. See Reinehr, Robert C., and Jon D. Swartz. The A to Z of Old Time Radio. Rowman & Littlefield, 2010. The show featured interviews with audience members who apparently were later presented with records of their interviews. Alas for Grossi, the record is proof of his impersonation of a U.S. Navy gunner’s mate. It is also proof of Grossi’s considerable skill at improvising fiction and snowing the unwary, featuring a long account of his imaginary combat career:

GROSSI: That is the silver star, five battles.

ANNOUNCER: Five of them! A silver star Oh Jack Can you tell us real quick what those five were. Can you remember them? You have got so many others here.

GROSSI: BIZEERTE NORTH AFRICA SICILY FRANCE UMANS Convoy Duty.

ANNOUNCER: Oh boy you were really busy there Jack. Now how about this middle ribbon What is that?

GROSSI Oh that’s South Pacific and Asiatic Pacific…

Two other interesting personal details also pop up in the transcript. Grossi annexes Harold Van Buren’s family line, declaring himself Van Buren’s nephew, employed as shipping manager in Van Buren’s jewelry business. And alas for Miss MB (not to mention Jack’s wife, whom we will meet below), Jack already has a girlfriend in Orange NJ. She works for the phone company and is listening to Glamour Mansion right now!

As for the parachute, that was something Grossi picked up when he hitched a ride from an Army transport plane. Apparently this was common in the immediate post-war period, and Grossi did it more than once (hitched a ride from an army transport, not absconded with a parachute). It is very difficult to figure out Grossi’s movements when he is taking these rides. This report marks the beginning of the FBI’s attempts to trace these.

Finally, Dallas checks with the First National Bank and gets a lead on another bad check from Grossi, this time from the Chicago USO. Which leads us to the next item.

Busted in Chicago

The next report is from SA Matthys in Chicago.20FBI file number 43-5359-17, released as ARC record 124-10204-10242 Checking with the USO, he finds that Grossi cashed the check on Jan. 23, still dressed as a gunner’s mate and using fake leave papers. Matthys then receives a Feb 12 teletype from Detroit concerning Grossi passing bad checks dressed as a gunner’s mate. By this time they had found out that there was no John Grossi in the US Navy and issued an arrest warrant for impersonation.

Detroit’s teletype also informs them that Grossi’s wife received a letter from him on Feb 6, with the return address of the Chicago Servicemen’s Center. Mr. Schultz at the Center advises that the name Grossi rings a bell, and they quickly realize that Grossi is still staying there. 45 minutes later Grossi walks in. Schultz calls the feds and Grossi is busted, wearing the beribboned uniform of a gunner’s mate and carrying the fake Navy id card and leave papers we saw in New Orleans.

Even better, Grossi’s suitcase is full of things like a Navy training corps certificate, certificate of eligibility to drive Navy vehicles, certificate of active service, pad of blank certificates of active service, orders to report for duty, a Florida driver’s license issued to Andrew Jack Williams, a book of universal form checks with 16 stubs, receipts for purchases, etc., etc.

Grossi freely admits to writing bad checks and gives a list of dates, places and amounts, but continues to maintain he is a member of the US Navy. At Grossi’s first hearing before the United States Commissioner, he says he will fight transfer to Detroit, but at the second hearing on Feb. 19 he gives up and agrees to removal, verbally admitting afterwards to SAs Matthys and Fetzner that he was never in the Navy. On Feb 27th he is removed to Detroit.21This item is immediately followed by a March 14th request to the FBI’s identification Division to make sure they’ve got all the information on Grossi’s criminal record. This is FBI file number 43-5359-18, released as ARC record 124-10204-10243

McEwing

It’s finally time to hear from Chester McEwing, who accompanied Grossi on his peregrinations from Philadelphia to Detroit and back.22FBI file number 43-5359-20, released as ARC record 124-10204-10245 The interview of McEwing gives an interesting picture of Grossi in motion, with a true gift for gab and grift.

McEwing meets Grossi at the Philadelphia Y, where M. has sought refuge from his wife. While drinking at a bar they pick up a third companion. catch a train to D.C. to look for girls, and to find the next place that can cash a check for Grossi. (Luckily they fail.)

Then back to Philly, where Grossi suggests a visit to Detroit, “a very fine city.” When McEwing tells Grossi he doesn’t have the train fare, Grossi replies he has plenty and will take care of him, which he does. To explain his funds, Grossi tells McEwing he draws cartoons for the Saturday Evening Post. McEwing finds this dubious, but does admit G. is a clever cartoonist.

Grossi glad hands his way to Motor City, making friends and cashing checks everywhere he can. After a couple of days in a hotel, McEwing suggests a visit to his navy friend Ziegler, but he is not home. His father Otto is, however, and welcomes them to stay “as long as they want.”

During their stay, Grossi averages one to two checks a day, with Mr. Ziegler himself endorsing the last two checks, written for over $300. At this point Grossi informs McEwing that he has overstayed his leave and needs to get back. G. forges leave papers while on the train back to avoid the long arm of the Shore Patrol.

From Philly they take another train to New York, where Grossi shmoozes with friends for a couple of hours, then catch a train to Baltimore, where Grossi calls his wife. McEwing hears Grossi arguing over the phone and takes his farewell.23The friends in New York are actually in Orange, N.J. a mother and her daughter who works for, yes, the phone company!

When the FBI catches up with him, the unhappy McEwing has just learned that Grossi shafted his friend’s father for over $300. He has set aside money from his salary to pay Mr. Ziegler back and also applied for sea duty to get more. (The interviewing agent checks to make sure this is true. It is.) The report’s authors then close with a RUC to their fellows in Detroit.

Newark digs up Jack’s past

I now have to skip around in the file a bit, since it is not in chronological order. We move next to a report from Newark giving the results of interviews with Grossi’s mother and the mysterious lady friend from New Jersey mentioned by McEwing.24FBI file number 43-5359-22, released as ARC record 124-10204-10247 This records also had redactions in it until the 2018 release, which is the version I cite here. The lady friend has little to say, except that she first met Grossi in August and last saw him a week before Christmas.

Grossi’s mother has more to say. She gives a capsule review of Grossi’s previous incarcerations and escapes from Jamesburg reformatory. She has also heard from her son’s new wife, who became Mrs. John Grossi in the last week of November. The younger Mrs. Grossi called her in the first week of December to let her know that Grossi had already left her and she was about to become a mother.

The last time Mother Grossi heard from her son was a letter from the Philadelphia Y dated Dec. 4. Her son, she tells SA Hodgens, has always been a problem, and she feels no responsibility whatever for any of his actions.

Newark closes with summaries of three interviews with people named in various other reports. VP last saw Grossi two years earlier and knows nothing more recent of him because his mother has forbidden him to see Grossi. Miss D. had several dates with Grossi two or three years ago, but has not had a letter from him in a year now. “The subject would write to her from all sorts of places, but would never furnish her a return address.” Miss P. also dated Grossi several times, but has not hear from him since January 1944. She was under the impression that he was in the Merchant Marines, which shows that Grossi was using this line even before he departed Jamesburg. Newark closes with an RUC to Detroit.

Baltimore reports

Baltimore is the epicenter of all this interviewing and investigating, but its report appears only after the interview with McEwing, apparently because they didn’t finish up until 3/13.25FBI file number 43-5359-21, released as ARC record 124-10204-10246

The report begins with a letter from Commander Shropshire, Naval Intelligence OIC in Baltimore, who has been contacted by another casher of Grossi checks. Shropshire, who does intelligence for a living, has collected a boatload of info about Grossi, which he dumps on the report’s author, SA Leach. In addition to Shropshire’s letter dated Jan. 30, teletypes from several other offices have also accumulated in Leach’s inbox, and he begins going through them on Feb. 5th.

Now up to speed on Grossi’s web of illicit activities, Leach calls Naval Intelligence Lt. Commander Kirby. Kirby provides the address of Mrs. Grabau, Mr. and Mrs. Grossi’s landlady, who naturally has detailed knowledge of her tenants’ personal affairs. The Grossis resided with her from Nov. 26 to Dec. 3, when Mr. G departed for Philly. He sent a telegram the same day promising Mrs. G. a letter and money. When the letter arrived, it said Mrs. G. should get a divorce, the marriage was a mistake: “he did not feel as though he could be tied down to her at this time.”

Yet on Dec. 20, Mr. G returned and the reunited couple left together for Florida, Mrs. G’s natal home. Or so says Mrs. Grabau, who received a letter from Mrs. G on Jan. 9. According to the letter, Mrs. G. is now working at Western Union Telegraph in Havana, FL, while Mr. G is on his way to another Navy assignment in the Great Lakes area.

At the end of what must have been a very long day, Leach makes one more call to the aggrieved check-casher who reported Grossi to Commander Shropshire in the first place: Mr. Collopy, a distributor for Acousticon (a hearing aid company). Collopy reports that Grossi came to his office on 11/26 to see if he could cash a $50 check, accompanied by Miss EJ, a cadet nurse who was a friend of Collopy’s wife. The check was of course drawn on the First National Bank of Dallas.

The next day, SA Leach pays a visit to Miss Coxe, director of nurses at Sinai Hospital. Miss EJ came to the hospital from her home in Florida the year before. After struggling in her classes, she withdrew on 11/26 because she was to be married the next day to Jack Grossi. One of her classmates actually attended the marriage, which took place in Bel-Air, Maryland on 11/27. Now Mrs. G., the former Miss EJ left a forwarding address in Tallahassee, FL.

The day after this, SA Leach is pounding the pavement again. Today he is visiting Mr. Stofbey, owner of a pharmacy who has two Grossi checks for a total of $85, acquired on Nov. 27 and 28. Mr. S. cashed these for the new Mrs. G. because he knew her as a a customer who was a cadet nurse at Sinai. Stofbey has shown a great deal of resourcefulness in dealing with this awkward situation. He has called Grossi’s mother and sister, and even attempted to contact 6131 Lakeshore Dr. in Dallas (Harold Van Buren’s residence) to see if the checks could be made good. Mrs. Grossi, he tells SA Leach, is certainly innocent of any deception; she had no idea the checks were worthless when she cashed them.

The same day,26The date is not very clear here, it could be Feb. 6, rather than Feb. 8. SA Leach contacts the Maryland Hotel, where Mr. and Mrs. G. spent five days after their wedding. SA Leach picks up their registration card for a handwriting sample and makes sure no bad checks were passed at the hotel.

Next stop is to see Sgt. Horton of the Baltimore check squad, who knows of yet another Grossi check, cashed at a jewelry shop. Copy obtained and sent to FBI lab. Horton also knows of a Grossi incident circa November, 1944, when Passaic, NJ requested Baltimore to look for three runaways: Jack Williams, aka Jack Grossi, age 17 at the time, and two other minors: JF and VP. They are located living at the Biltmore Hotel. JF and VP are returned to Jersey, but Grossi is not.27Note that Grossi is already giving Van Buren’s residence in Dallas as his home address. This VP is the same one interviewed in an earlier serial by the FBI’s Newark office.

Final stop of another long day is Mr. Overbeck’s jewelry store, where SA Leach talks to the salesman who got stuck with the bad check Sgt. Horton provided. Grossi and another young man came to the store to purchase a ring. Skipping the ring, however, they ask the store to cash a check from Harold Van Buren, made out to Grossi. Said salesmen has Grossi endorse the check and carefully checks the against the signature on Grossi’s fake Navy ID: “he stated that so far as he knew, the ID had been properly issued to the sailor.”

Baltimore is now ready to sum up the case. Already on Feb. 6 they have sent teletypes to various and sundry offices, advising them of Grossi’s activities. They ask Newark to interview all these Jersey kids, and Miami to find and interview Mrs. Grossi. On Feb. 12th, they send the four bad checks Leach acquired to the FBI lab to check against the Bureau’s Fraudulent Check File28See Unlocking the Files of the FBI: A Guide to Its Records and Classification System. Scholarly resources, 1993, p. 236. and also handwriting samples from Mr. and Mrs. G.

On March 1 the Lab reports results on 3 checks from Detroit, 1 check from Atlanta, 1 check from Chicago, and 4 checks from Baltimore. All checks signed by Grossi were signed by Grossi; all checks signed by Mrs. G were signed by Mrs. G. Search in the National Fraudulent Check File reveals no matches.

All of this stuff is added to the file, along with more teletypes from Detroit, informing Baltimore of Grossi’s arrest in Chicago and Detroit’s plans to prosecute for impersonation. The whole shebang is then dropped on the Baltimore USA (US Attorney), who shrugs and says render unto Detroit that which is Detroit’s; I’ve got other things to do. The report closes with yet another description of Grossi and his primary family members.

End of the story

One investigative thread remains in the file: believe it or not, Detroit actually sends New York out to track down and interview the producer and host of Glamour Manor.29FBI file number 43-5359-23, released as ARC record 124-10204-10248 The producer does indeed have a copy of the recording of Grossi impersonating a USN sailor on the show; this can serve as evidence if Grossi goes to trial. The program host on August 22 was Miss Patricia Bell, who advises that she has “no recollection whatsoever” of Grossi. “he possibly was one of the many who appeared on the program. However she had no personal knowledge of him.” Nor are there any photos remaining of Grossi in his gunner’s mate uniform. New York ends with an RUC to their brothers in Detroit.

Grossi spends several weeks cooling his heels in the Detroit lockup. He is indicted on charges of impersonation and IWU on April 12.30FBI file number 43-5359-25, released as ARC record 124-10204-10250. This version of the document was released in 1995 and redacts several paragraphs dealing with Grossi’s juvenile records. These were released in 2017-2018 and are available here. He finally asks to talk to a lawyer. After some negotiations, he is re-indicted on April 15 on the impersonation charge, and the IWU charge is dropped. He is then sentenced to two years in a federal prison (later files show it was the Terre Haute USP).

As part of the deal, he gives a detailed statement of how he got all the phony documents found in his bags in Chicago. His statement begins with the surprising announcement that he really was in the Merchant Marines for three years. More on this below. For the fake Navy documents, he picked up the blank service certificates in the Jacksonville FL recruiting station in Jan of 1946 (must have been when he went down to Florida with his wife). He filled out one of these himself in FL. Ditto for most of the other certificates he had. His service card he picked up in the Newark USO in the summer of 1945. It was at this point he started parading around in a USN uniform (he says). Previously he had only worn his USMS outfit.

Back to the USMS. According to Grossi’s account in his statement, he joined the Merchant Marines in August 1941. He used the alias Jack Dale Williams because he had been in a state home. He was 18 at the time. Somehow they found out he was not who he said he was, and he was given an honorable discharge from the USMS in Jan. 1944 in New York. He tried to enlist in the Navy in 1945 but was rejected because he was still held officially in custody as a juvenile. He registered with the NJ Draft Board in Aug 1941 and was classified 1A.

Of course none of this is true, but that didn’t stop Grossi from making these claims in his official statement. The statement is followed by a parole report dated 5/28 that runs down Jack’s real background and record. It makes no recommendations.

The file closes with an anti-climax, a long series of documents dating from the end of 1947 about the parachute that Grossi nicked after hitching a ride on Army air transport.31The FBI’s tale of tracking down the parachute starts with FBI file number 43-5359-19, released as ARC record 124-10204-10244. The Army later becomes convinced that the FBI has detained their parachurte as evidence and there is a testy exchange of teletypes that ends in HQ throwing all the correspondence into a big enclosure to keep Army from hassling them about the damn parachute anymore (See FBI file number 43-5359-26, released as ARC record 124-10204-10251; FBI file number 43-5359-27, released as ARC record 124-10204-10252; FBI file number 43-5359-28, released as ARC record 124-10204-10253; FBI file number 43-5359-29, released as ARC record 124-10204-10254).

The final item recorded in the file is from 1949. New York informs HQ that it has canceled holds placed on Grossi traveler’s checks.32FBI file number 43-5359-30, released as ARC record 124-10204-10255 I can’t make much sense out of this. Grossi did buy some traveler’s checks with his bad paper, but the reference to the Salt Lake office is puzzling. I wonder if this particular document might be related to some other, later case.

Grossi file issues

A surprising problem with casefile 43-5359 is that it is not listed in the ACRS. The ACRS is NARA’s online database of ARC finding aids and should contain metadata for all ARC records released from 1993 on. All of the records in case 43-5359, however, are on one of three disks of FBI metadata which were not transferred to the ACRS. I have a previous post on this problem here. This omission has made research on this particular FBI file confusing and difficult. I will vent my dissatisfaction right below.

Fortunately, the MFF has inventories for all of the Grossi files in the ARC.33Oddly, there are three versions of the inventory for 43-5359, two of them partial. The only complete one is here. It seems that the inventories are not part of the ARC, or at least have no RIF number. Although their status is unclear to me, they provide a good part of the information that the ACRS does, in some respects more. I will try to post on this in the future.

Another issue with 43-5359 is that the entire first eight serials from the file were withheld in full until the 2017-2018 ARC releases.34These are numbered serials. Many casefiles also include unnumbered serials. These are indicated with the letters NR. 43-5359 has three of these that were withheld as well: 43-5359-1ST NR 3 (ARC 124-10204-10226), 43-5359 1ST NR 7 (ARC 124-10204-10231), and 43-5359-1ST NR 8 (ARC 124-10204-10233). These all deal with “Thomas Herman”, the juvenile who was arrested with Grossi in 1944. I omit these, since Herman had nothing to do with Grossi sponsoring Lee Oswald for a Dallas library card in 1963. The original “release” of these files in 1995 consisted of a RIF sheet for each document and a notice that all the content was being withheld, with a cryptic reference at the bottom to 10(a)1.35See for example 124-10204-10223.

Section 10(a)1 of the ARCA, the act which established the ARC, deals with records under seal of court. Unfortunately, there is no detailed listing of what sort of materials in the Collection were held under seal of court, and this has led to various random guesses about what Grossi’s withheld records contained. As the 2017-2018 releases have made clear, all of the documents with 10(a)1 postponements in Grossi’s files are juvenile criminal records. I have looked in the ACRS for other instances of 10(a)1 materials, and it is clear that they are NOT limited to juvenile records. I will post further on this in the very near future. Notice, however, that a search of the ACRS for 10(a)1 material will NOT turn up Grossi’s file 43-5359. The metadata for all documents from this file was on one of the three scrongled FBI disks mentioned above and discussed in my previous post. The spreadsheet from NARA giving metadata for the 2017-2018 is also blank for all fields for these records except the RIF numbers, making it even harder to figure out they’ve actually been released. This problem needs to be fixed.

The inclusion of juvenile records in the ARC opens up a tangled thicket of issues. It is one aspect of a very general problem in the ARC: how to handle the conflict between public records and individual privacy. I will eventually get around to posting on this, but I should tell you, that post has been on my list of things to do for over two years now.

Footnotes

- 1CE 427 (17 H 156) gives October 12, 1962 as Oswald’s date of employment and has a note that he was terminated April 6, 1963. Testimony from several JCS employees can be found in 10 H 167-213. For those looking up JCS online, Jaggars is very frequently misspelled “Jaggers”. The correct spelling, as given in the WC hearings, is with an “a”.

- 2The file in excerpted in Commission Document 205, p. 469

- 3ARC record 124-10208-10266, p. 17

- 4FBI file 43-5359-1, released as ARC record 124-10204-10223. This is one of the few examples in the ARC of an FBI case file for IWU (classification 43), which is to be distinguished from impersonation (classification 47). Apparently impersonation was more serious, but also more difficult to prove. In the end, however, through an odd fluke, Grossi was nailed not for IWU, but for impersonation. See Haines, Gerald K., and David A. Langbart. Unlocking the Files of the FBI: A Guide to Its Records and Classification System. Scholarly resources, 1993 for a general description of the category.

- 5FBI file number 43-5359-2, released as ARC record 124-10204-10224

- 6FBI file number 43-5359-3, released as ARC record 124-10204-10225.

- 7This comes from 43-5359-25, released as ARC record 124-10204-10250. Since Grossi was 15 at the time, this was also treated as a juvenile record and withheld until 2018, when these redactions were finally released by NARA

- 8FBI file number 43-5359-4, released as ARC record 124-10204-10227.

- 9The inventory is apparently not part of the ARC

- 10FBI file number 43-5359-6, released as ARC record 124-10204-10229.

- 11FBI file number 43-5359-7, released as ARC record 124-10204-10230.

- 12FBI file number 43-5359-8, released as ARC record 124-10204-10232.

- 13See the 2018 release of ARC document 124-10204-10250

- 14FBI file number 43-5359-9, released as ARC record 124-10204-10234.

- 15FBI file number 43-5359-10, released as ARC record 124-10204-10235.

- 16FBI file number 43-5359-11, released as ARC record 124-10204-10236

- 17The lab requests and reports include FBI file number 43-5359-12, released as ARC record 124-10204-10237, FBI file number 43-5359-13, released as ARC record 124-10204-10238, and FBI file number 43-5359-14, released as ARC record 124-10204-10239. The Atlanta report is FBI file number 43-5359-15, released as ARC record 124-10204-10240

- 18FBI file number 43-5359-16, released as ARC record 124-10204-10241

- 19The “Glamour Manor” program is now lost in mists of history, except to the fans of old time radio. See Reinehr, Robert C., and Jon D. Swartz. The A to Z of Old Time Radio. Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

- 20FBI file number 43-5359-17, released as ARC record 124-10204-10242

- 21This item is immediately followed by a March 14th request to the FBI’s identification Division to make sure they’ve got all the information on Grossi’s criminal record. This is FBI file number 43-5359-18, released as ARC record 124-10204-10243

- 22FBI file number 43-5359-20, released as ARC record 124-10204-10245

- 23The friends in New York are actually in Orange, N.J. a mother and her daughter who works for, yes, the phone company!

- 24FBI file number 43-5359-22, released as ARC record 124-10204-10247 This records also had redactions in it until the 2018 release, which is the version I cite here.

- 25FBI file number 43-5359-21, released as ARC record 124-10204-10246

- 26The date is not very clear here, it could be Feb. 6, rather than Feb. 8.

- 27Note that Grossi is already giving Van Buren’s residence in Dallas as his home address. This VP is the same one interviewed in an earlier serial by the FBI’s Newark office.

- 28See Unlocking the Files of the FBI: A Guide to Its Records and Classification System. Scholarly resources, 1993, p. 236.

- 29FBI file number 43-5359-23, released as ARC record 124-10204-10248

- 30FBI file number 43-5359-25, released as ARC record 124-10204-10250. This version of the document was released in 1995 and redacts several paragraphs dealing with Grossi’s juvenile records. These were released in 2017-2018 and are available here.

- 31The FBI’s tale of tracking down the parachute starts with FBI file number 43-5359-19, released as ARC record 124-10204-10244. The Army later becomes convinced that the FBI has detained their parachurte as evidence and there is a testy exchange of teletypes that ends in HQ throwing all the correspondence into a big enclosure to keep Army from hassling them about the damn parachute anymore (See FBI file number 43-5359-26, released as ARC record 124-10204-10251; FBI file number 43-5359-27, released as ARC record 124-10204-10252; FBI file number 43-5359-28, released as ARC record 124-10204-10253; FBI file number 43-5359-29, released as ARC record 124-10204-10254).

- 32FBI file number 43-5359-30, released as ARC record 124-10204-10255

- 33Oddly, there are three versions of the inventory for 43-5359, two of them partial. The only complete one is here.

- 34These are numbered serials. Many casefiles also include unnumbered serials. These are indicated with the letters NR. 43-5359 has three of these that were withheld as well: 43-5359-1ST NR 3 (ARC 124-10204-10226), 43-5359 1ST NR 7 (ARC 124-10204-10231), and 43-5359-1ST NR 8 (ARC 124-10204-10233). These all deal with “Thomas Herman”, the juvenile who was arrested with Grossi in 1944. I omit these, since Herman had nothing to do with Grossi sponsoring Lee Oswald for a Dallas library card in 1963.

- 35See for example 124-10204-10223.